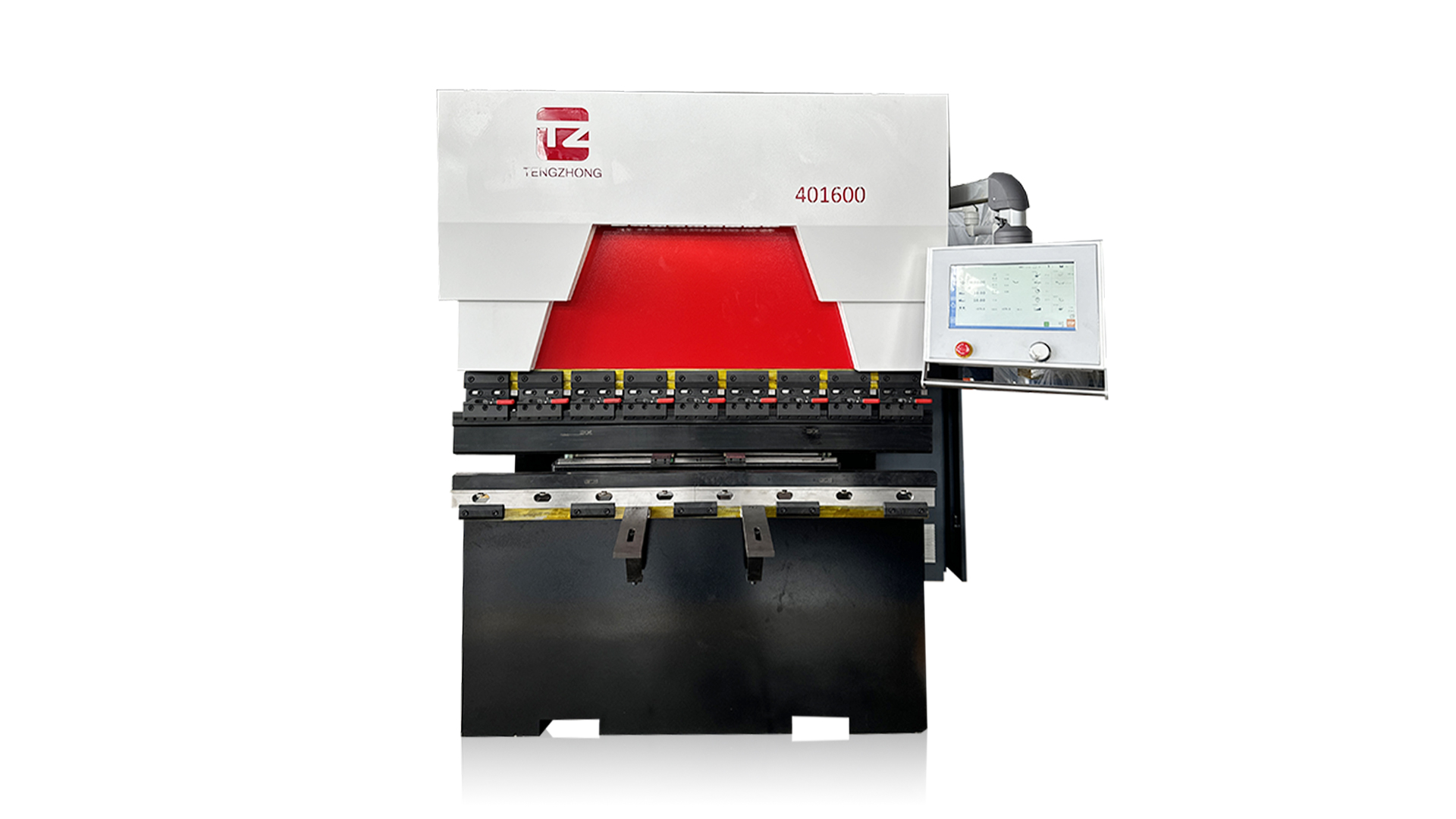

Press Brake Machine: Types, Specs & How to Choose the Right One

2026-02-20

What Is a Press Brake Machine?

A press brake machine is a piece of metal fabrication equipment used to bend and form sheet metal into precise angles and shapes by clamping the workpiece between a matching punch and die. It is one of the most essential tools in metal fabrication shops, manufacturing plants, and HVAC industries. Press brakes can produce bends with tolerances as tight as ±0.1°, making them indispensable for applications that demand high precision.

The machine works by applying controlled force — ranging from a few tons to over 3,000 tons on industrial models — to deform metal along a straight axis. Whether you're bending 0.5 mm aluminum sheets or 25 mm thick steel plates, the right press brake machine can handle the job efficiently and repeatedly.

Types of Press Brake Machines

Press brakes come in several configurations, each suited to different production demands, material types, and budget ranges. Understanding the distinctions helps you choose the right machine for your operation.

Hydraulic Press Brake

The most widely used type in heavy fabrication. Hydraulic press brakes use oil-driven cylinders to generate force and offer tonnage capacities from 40 to 3,000+ tons. They are known for their reliability and ability to handle thick materials. However, they consume more energy compared to electric models and require periodic maintenance of the hydraulic system.

Electric Press Brake (All-Electric)

Driven by servo motors, electric press brakes are growing in popularity due to their energy efficiency — typically consuming 30–50% less energy than hydraulic models. They offer faster stroke speeds, cleaner operation (no hydraulic oil risk), and superior repeatability. They are best suited for thin to medium gauge materials and high-mix, low-volume production environments.

Electro-Hydraulic (Hybrid) Press Brake

Hybrid press brakes combine hydraulic power with electric servo control. They deliver the high tonnage of hydraulic systems with the energy savings and precision of electric drives. Many modern CNC press brakes fall into this category, and they are favored in shops that need both versatility and efficiency.

Mechanical Press Brake

Older technology using a flywheel and clutch mechanism. Mechanical press brakes are fast but less flexible and harder to control precisely. They are largely being phased out in favor of CNC hydraulic and electric models in modern facilities, though some shops retain them for simple, high-speed repetitive bends.

Key Specifications to Understand

Before purchasing or operating a press brake machine, it's critical to understand the core specifications that define its capability and suitability for your application.

| Specification | Definition | Typical Range | Why It Matters |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tonnage | Maximum bending force | 40 – 3,000 tons | Determines max material thickness and type |

| Bending Length | Max workpiece width | 1,000 – 8,000 mm | Limits the length of the part that can be formed |

| Stroke Length | Ram vertical travel distance | 100 – 300 mm | Affects clearance for deep boxes and profiles |

| Open Height | Distance between beam and table at full open | 350 – 600 mm | Determines the size of parts that can be inserted |

| Back Gauge Depth | CNC-controlled material stop distance | up to 750 mm | Controls flange length accurately |

| CNC Axes | Number of controlled motion axes | 2 – 12+ axes | More axes = more automation and flexibility |

When calculating the required tonnage for a job, the general rule of thumb is: 1 ton per 12 mm of die opening per 1 meter of bending length for mild steel of 1 mm thickness. For stainless steel, multiply the result by approximately 1.5; for aluminum, use about 0.5 as a factor.

How a Press Brake Machine Works

The bending process involves three core components: the punch (upper tool), the die (lower tool), and the ram (beam) that drives the punch downward. Here is a step-by-step breakdown of the typical bending cycle:

- The operator or robot loads the flat sheet metal onto the press brake bed.

- The back gauge positions the material to the programmed flange depth.

- The operator activates the cycle (via foot pedal or automatic trigger on robotic cells).

- The upper beam descends, driving the punch into the sheet metal and forcing it into the die opening.

- The CNC controller monitors and adjusts the ram position to achieve the programmed bend angle, compensating for springback automatically on advanced models.

- The ram retracts, the material is repositioned (manually or via CNC back gauge), and the next bend is made.

Modern CNC press brakes use real-time angle measurement systems — such as laser angle sensors or contact-type probes — to detect springback and automatically over-bend to compensate, eliminating the need for manual trial bends and significantly reducing setup scrap.

Air Bending vs. Bottom Bending vs. Coining

The three primary bending methods used in press brake operations differ significantly in force requirements, tool life, and accuracy:

- Air bending: The punch presses the metal into the die without fully bottoming out. It requires the least force and allows a wide range of angles with the same tooling. Most modern CNC press brake work uses air bending.

- Bottom bending: The material is pressed to touch the die walls, requiring 3–5× more force than air bending but achieving tighter angular tolerances. Springback is more consistent and easier to predict.

- Coining: The punch fully embeds into the material surface under very high pressure (5–30× air bending force), virtually eliminating springback. It achieves the highest precision but accelerates tool wear and demands the highest tonnage.

CNC Press Brake: Capabilities and Advantages

CNC (Computer Numerical Control) press brakes represent the current industry standard for precision metal forming. They allow operators to program complex bend sequences, store hundreds of part programs, and achieve highly repeatable results across long production runs.

A typical modern CNC press brake includes a graphical controller (such as Delem DA-66T, Cybelec, or ESA) that allows operators to input part geometry directly, automatically calculate bend sequences, and simulate the bending process before a single cut is made. Setup times can be reduced by up to 60% compared to manual press brakes, especially for complex parts requiring multiple bends.

Typical CNC Axis Configuration

- Y1/Y2 axes: Left and right ram positioning for crowning correction and parallelism control.

- X axis: Back gauge horizontal movement for flange depth control.

- R axis: Back gauge vertical movement to accommodate different die heights.

- Z1/Z2 axes: Lateral back gauge movement for angled or asymmetric bending.

- V axis (crowning): Automatic bed deflection compensation to maintain uniform bend angle across the full length.

High-end models from manufacturers like TRUMPF, Bystronic, Amada, and LVD offer up to 12 CNC axes, integrated tool changers, and adaptive bending systems that measure the actual bend angle in real time and self-correct during the stroke.

Press Brake Tooling: Punches and Dies

The punch and die set you select directly determines the bend quality, minimum flange length, and achievable inside radius. Investing in quality tooling is often as important as the machine itself.

Common Punch Types

- Standard (gooseneck) punch: The most versatile punch shape, designed to provide clearance for box flanges and standard bending.

- Acute angle punch: Allows bends beyond 90°, typically ground to 30° or 45° tip angles for tight profile work.

- Radius punch: Features a large rounded tip to produce sweeping radius bends without a visible bend line, common in furniture and architectural panels.

- Flattening/hemming punch: Used for closing hems and seams on sheet metal edges.

Die Opening Selection

Die opening width is critical to both quality and force requirements. The standard guideline is to use a die opening of 8× the material thickness for mild steel air bending. For example, bending 3 mm mild steel ideally uses a 24 mm V-die. Going too narrow increases the required tonnage and risks surface marking; too wide produces poor angular accuracy.

Tooling systems like Wila and Wilson Tool International offer modular precision tooling with safety locks, hardened and ground surfaces (typically hardened to 56–62 HRC), and quick-change adapters that can reduce tool change time from 20 minutes to under 2 minutes.

Common Applications of Press Brake Machines

Press brake machines are used across a wide range of industries where precision-formed sheet metal components are required. Some of the most common application areas include:

| Industry | Typical Materials | Example Parts | Typical Tonnage |

|---|---|---|---|

| HVAC / Ductwork | Galvanized steel, aluminum | Duct sections, flanges, transitions | 40–100 tons |

| Construction / Architecture | Stainless steel, aluminum cladding | Facade panels, brackets, frames | 100–250 tons |

| Automotive | High-strength steel, aluminum | Chassis parts, brackets, enclosures | 100–500 tons |

| Electronics / Enclosures | Cold-rolled steel, stainless | Server racks, control panels, cabinets | 40–160 tons |

| Heavy Equipment | Structural steel, AR plate | Booms, chassis beams, tanks | 400–3,000 tons |

Safety Considerations for Press Brake Operation

Press brakes are powerful machines that require strict adherence to safety protocols. According to OSHA and industry safety data, press brake-related injuries account for a significant share of severe hand and finger injuries in metalworking facilities. Modern machines address this through multiple layers of safety systems.

Active Safety Systems

- Laser guarding systems (e.g., LPA, AKAS): Project a laser curtain just below the punch tip. If anything interrupts the beam during the closing stroke, the machine stops within milliseconds — with stopping distances as short as 1–2 mm.

- Light curtains: Mounted to the machine frame to detect any intrusion into the bending zone during operation.

- Two-hand control: Requires both hands to activate and hold the cycle, keeping them away from the bending area.

- Safe speed mode (muting): Allows the operator to approach the mute point (bend point) at high speed and automatically slows the ram for the final closing stroke when the operator's hands may be near the tooling.

Operator Best Practices

- Always verify tool clamp security before running a program, especially after a tool change.

- Never reach into the bending zone while the machine is in cycle — even with active guarding in place.

- Use proper personal protective equipment: safety glasses, steel-toed boots, and cut-resistant gloves when handling sheet metal.

- Conduct a dry run (no material) when loading a new program to verify back gauge positions and ram travel.

- Ensure tonnage settings do not exceed the rated capacity for the die section in use — overloading a short section of tooling is a leading cause of tooling fracture.

How to Choose the Right Press Brake Machine

Selecting the right press brake comes down to matching the machine's capabilities to your production requirements — both current and anticipated. Here are the most important factors to evaluate:

Material and Thickness Range

Define the full range of materials you intend to bend — gauge of aluminum sheet for light enclosures up to thick structural steel. Size the machine for your maximum expected job, not your average job. A common mistake is undersizing and discovering the machine cannot handle new contracts that arrive six months after purchase.

Production Volume and Mix

High-volume, low-mix production (e.g., running the same part all day) favors simpler or older mechanical machines. High-mix, low-volume job shops benefit greatly from CNC press brakes with fast setup, offline programming, and automatic back gauges. If you run more than 10 different part numbers per day, a CNC press brake with a modern controller typically pays back its premium within 12–18 months through reduced setup time and scrap.

Degree of Automation

Robotic press brake cells (e.g., Bystronic's Xpert 150, Amada's HG-ATC series with automatic tool changers) offer lights-out bending for medium-volume production. For shops experiencing labor shortages or pursuing Industry 4.0 integration, robotic bending cells can deliver 3–4× the throughput of a manually-operated machine for repeatable part families.

Budget and Total Cost of Ownership

Entry-level CNC hydraulic press brakes start at around $30,000–$60,000 for a 40-ton, 1.2-meter machine from Chinese manufacturers such as Anhui ACCURL or Durma. Mid-range European and Japanese machines (Amada, Trumpf, LVD, Bystronic) in the 100-ton class typically cost $150,000–$400,000. When comparing, factor in tooling costs, energy consumption, preventive maintenance schedules, and the availability of local service technicians — not just the purchase price.

Maintenance and Troubleshooting Basics

A well-maintained press brake can deliver reliable performance for 20–30 years. Establishing a preventive maintenance routine dramatically reduces unplanned downtime and extends the life of both the machine and its tooling.

Routine Maintenance Checklist

- Daily: Check hydraulic oil level and temperature, inspect tool clamping security, clean the back gauge rails, verify laser safety system operation.

- Weekly: Lubricate back gauge lead screws and guide rails, check hydraulic hoses for leaks or abrasion, inspect ram parallelism and adjust if deviation exceeds 0.02 mm/m.

- Monthly: Replace hydraulic return-line filter elements, check servo motor encoder feedback, clean and inspect CNC controller ventilation filters.

- Annually: Full hydraulic oil change (or per manufacturer's hour-based schedule), complete machine geometry calibration, back gauge positioning accuracy verification.

Common Issues and Solutions

- Inconsistent bend angles: Usually caused by worn tooling, incorrect crowning compensation, or material hardness variation. Recalibrate the V-axis crowning and inspect punch tip radius wear.

- Twisting or bowing after bending: Indicates non-parallel ram or uneven die seating. Check Y1/Y2 axis synchronization and die clamp integrity.

- Back gauge positioning errors: Often a worn ball screw or lost encoder reference. Run a homing cycle and check backlash against tolerance specs.

- Slow or sluggish ram movement: Typically low hydraulic oil, clogged filter, or cold hydraulic fluid in winter. Warm up the machine at low pressure before production in cold climates.

English

English русский

русский Français

Français Español

Español Português

Português عربى

عربى